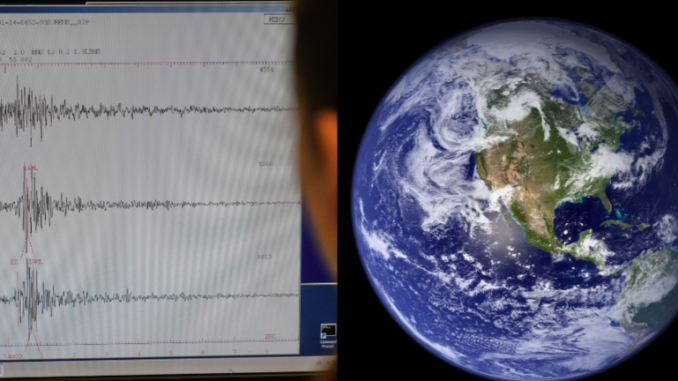

The world was struck with abnormal seismic waves earlier this month, and scientists are still baffled as to why.

On November 11, at 9:30am UTC, a mysterious rumble travelled thousands of kilometres around the globe, setting off sensors throughout Africa, New Zealand, Canada, and Hawaii.

These seismic waves began roughly 15 miles off the shores of Mayotte, a French island which is situated between Africa and the northern tip of Madagascar. The waves then travelled almost 11,000 miles away from their point of origin – without a single human feeling them.

BYPASS THE CENSORS

Sign up to get unfiltered news delivered straight to your inbox.

You can unsubscribe any time. By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use

Luckily, an earthquake enthusiast in New Zealand who had been tuned in to the US Geological Survey’s real-time seismogram displays online spotted them as they occurred.

Abc.net.au reports: They posted images of the readings to Twitter, prompting researchers around the world to try to deduce where these bizarre waves came from.

This is a most odd and unusual seismic signal.

Recorded at Kilima Mbogo, Kenya …#earthquakehttps://t.co/GIHQWSXShd pic.twitter.com/FTSpNVTJ9B— ******* Pax (@matarikipax) November 11, 2018

Unlike traditional earthquakes, which produce a jolt of various high frequency waves, the readings from the Mayotte tremor picked up consistent low frequency waves that lasted more than 20 minutes. It was as though the planet rang like a bell.

Online theorists suggest covert nuclear tests, sea monsters, or a meteorite as the cause of the tremor, but Goran Ekstrom, a seismologist at Columbia University, told National Geographic the explanation was likely straight-forward.

Professor Ekstrom suggests that the seismic event actually did begin with an earthquake. He thinks it passed by surreptitiously because it was a slow earthquake.

Slow earthquakes are quieter than traditional quakes because they come from a gradual release of stress that can stretch over a significant period of time.

“The same deformation happens, but it doesn’t happen as a jolt,” Professor Ekstrom said.

Since May this year, Mayotte has been subjected to what is known as an ‘earthquake swarm’; a cluster of hundreds of seismic events over a period of days or weeks, but the activity has significantly lessened in recent months.

Analysis by the French Geological Survey suggests the strange waves may indicate a mass movement of magma beneath the earth’s crust, such as a chamber collapse.

Rhythmic motion, like sloshing of the molten rock, or a pressure wave ricocheting through the magma body have the potential to resonate in a similar way to the Mayotte readings.

The Democratic Republic of Congo was the site of a similar event in 2002, where a similar slow earthquake and low-frequency waves were linked with a magma chamber collapsing below the Nyiragongo volcano.