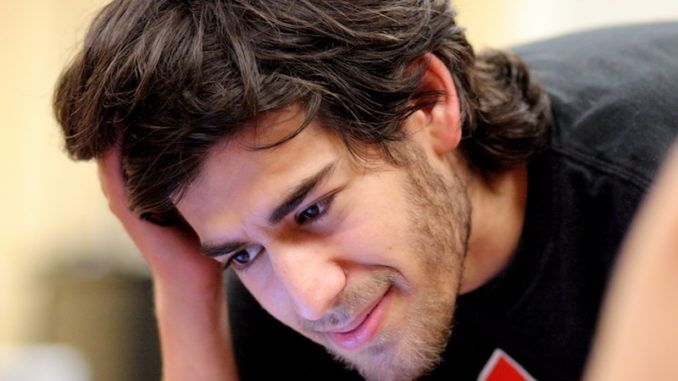

The FBI began actively spying on Reddit founder Aaron Swartz two years earlier than previously thought.

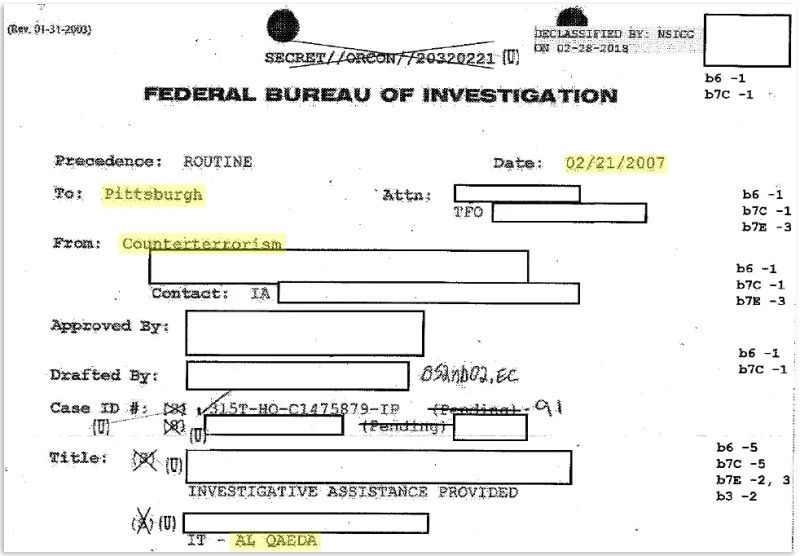

According to a document first published by Gizmodo, the FBI secretly collected Swartz’ email data in a counterterrorism investigation that also ensnared students at an American university.

Gizmodo.com reports: The email data belonging to Swartz, who was likely not the target of the counterterrorism investigation, was cataloged by the FBI and accessed more than a year later as it weighed potential charges against him for something wholly unrelated. The legal practice of storing data on Americans who are not suspected of crimes, so that it may be used against them later on, has long been denounced by civil liberties experts, who’ve called on courts and lawmakers to curtail the FBI’s “radically” expansive search procedures.

BYPASS THE CENSORS

Sign up to get unfiltered news delivered straight to your inbox.

You can unsubscribe any time. By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use

In November 2008, days before Swartz’s 22nd birthday, FBI investigators were combing the internet for any information they could find on the young man fated to become one of the internet’s most celebrated figures. At the time, the bureau was working to determine whether Swartz had violated any laws when he downloaded millions of court documents from an online system known as PACER.

The FBI would ultimately conclude that no crime had been committed and that the court records already belonged to the public. (Some three years later, the U.S. government charged him with crimes related to mass-downloading from another database.) But on that day in November, the investigators would leave no stone unturned.

Drawing from information published on Wikipedia and using investigative tools such as Accurint, FBI employees began quietly building a profile of the oft-described technology “wunderkind,” noting, for example, his involvement in the creation of the formatting language Markdown and RSS 1.0, and jotting down the various code frameworks that Swartz had helped to create and organizations that he had helped to found. Eventually, with all open source avenues exhausted, an FBI employee sat down at a computer terminal that, to most people, would appear plucked straight from the 1980s. The employee ran a search using the bureau’s automated case support system, a portal to the motherlode of FBI investigative files.

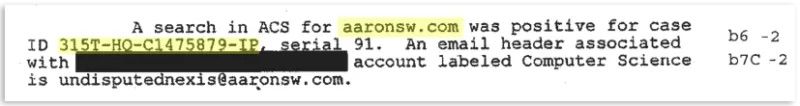

When the FBI worker typed in Swartz’s internet domain—aaronsw.com—he got a hit. A single file popped up bearing the case number 315T-HQ-C1475879. The prefix, 315, is a numerical classifier that was assigned to the file when it was created nearly two years before. It told the FBI employee that Swartz’s domain was linked, though not precisely how, to an international terrorism case. And then they cracked it open.

315T-HQ-C1475879

This case has been something of a mystery since its existence was first unearthed by journalists and researchers who engaged the FBI in lengthy court battles over records related Swartz, a celebrated internet rights activist, who, while being targeted by overzealous prosecutors in January 2013, died by suicide.

As mentioned, the newly released document, obtained first in a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit by transparency group Property of the People, reveals that Swartz was already of investigative interest to the FBI years before he was criminally charged with downloading millions of articles and documents from JSTOR, an expansive digital library of academic journals, in early 2011 and, more importantly, nearly two years before the Justice Department considered charges against him related to his PACER activity—the first known law enforcement probe to involve him, until now.

The FBI has long argued in favor of growing its profound authority to acquire Americans’ private communications data in huge quantities without a judge’s approval. But the document obtained by Property of the People, which was formerly classified “secret,” appears to exemplify, using a rather high-profile figure, the many inherent risks in allowing police agencies to secretly stockpile data on innocent Americans in the name of national security.

The document appears to show that in early 2007, the FBI cataloged a substantial amount of email metadata from the computer science and IT departments of the University of Pittsburgh, citing as justification the pursuit of a terrorism lead.

The terrorist group at the center of the investigation is also identified by name—Al Qaeda.

That any information about Swartz was collected during an Al Qaeda investigation—only to be retrieved nearly two years later for totally unrelated purposes—adds a familiar and sympathetic face to a controversial procedure in intelligence gathering commonly referred to as a “backdoor search.” That is, the FBI gathering information about Americans who are not accused of crimes, often without a warrant; storing that information in databases, sometimes for years; and later accessing it during the course of another investigation that ultimately has nothing to do with terrorism whatsoever. (Backdoor searches are most commonly associated with Section 702 of the FISA Amendments Act, an authority that was unavailable to the FBI at the time.)

While the substantive details of this terrorism investigation remain a mystery, legal experts who spoke to Gizmodo said they were alarmed—but not the least bit surprised—to hear the FBI used information gleaned in a terrorism case as it tried to build a criminal one against Swartz long after.

“It’s disturbing that the FBI is mining this information for unrelated criminal investigations that have nothing to do with why it was collected in the first place,” said Neema Singh Guliani, the American Civil Liberties Union’s legislative counsel. This practice, she said, is another example “of the way in which this authority has been abused by the government and underscores the need for reform.”

Certain types of electronic information, most of which can be described as “metadata,” may be acquired by the FBI without a warrant, provided it certifies there’s a “specific and articulable” link to suspected terrorist activities. This is basically the legal equivalent of a hunch, a threshold which is floors below probable cause. And this key: Obtaining that same information under any other circumstance—except in the case of espionage—would otherwise require a court order.

How specifically the FBI came to possess Swartz’s email data remains unclear.

But after reviewing the document and other related files, several legal experts told Gizmodo the most likely explanation was that the FBI had used a National Security Letter (NSL), a ubiquitous tool for obtaining email header data at the time. An NSL would have enabled federal agents to demand access to the data and then impose a gag order to maintain secrecy around the investigation, all without a judge’s approval.

Authorized under the Stored Communications Act, in cases of suspected terrorism or espionage, these letters enable the FBI to seize a variety of electronic records under its own authority. While agents cannot use an NSL to acquire the contents of an email message, the FBI’s notes appear to show that, in Swartz’s case, it sought only “email headers,” data the FBI would argue falls well within the scope of its power to seize.

Property of the People co-founder Ryan Shapiro, who holds a PhD from MIT, told Gizmodo that the Justice Department was “particularly aggressive” in court while trying to keep its prior, and formerly undisclosed, investigative interest in Swartz under wraps. It only relented, he said, when it seemed the U.S. attorney feared an unfavorable ruling, which could impact the Justice Department in future court cases.

“The FBI does nearly everything in its power to maintain its functional immunity from the Freedom of Information Act. As one element of its anti-FOIA efforts, the FBI is notorious for the deliberate poverty of its FOIA searches,” he said. “In this case, the Bureau even made the ludicrous claim that documents about Aaron Swartz’s email address, email header data, and domain weren’t related to him, and therefore were outside the scope of the FBI’s search for records about Swartz. It took us years of litigation to force the FBI to finally search for and even partially release this important document.”

The FBI declined to comment on the case and instead pointed to Justice Department guidelines that define the scope of the FBI’s authority. “The manner in which the FBI acquires information must meet a legal threshold, and the use of that information is governed by legal statutes and guidelines on investigations established by the Attorney General. In addition, the FBI’s use of its legal authorities is subject to robust oversight by all three branches of government,” it said.

University snooping

While heavily redacted, the document obtained by Property of the People offers multiples clues as to the origin of the collected email data. It almost certainly originated from the University of Pittsburgh (PITT). At the time of writing, however, it remains unknown what connected the University to an investigation involving Al Qaeda in 2007. (Several key portions of the records are redacted, with exemptions referencing the National Security Act of 1947.)

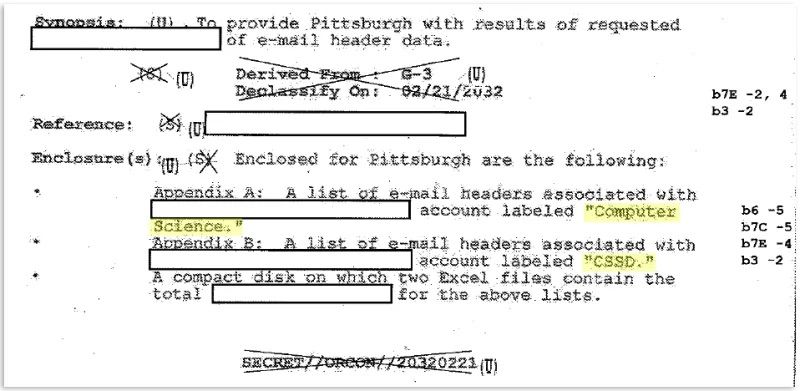

Notably, the document references two sets of email data labeled “Computer Science” and “CSSD” (“Appendix A” and “Appendix B,” respectively).

While “Computer Science” is admittedly ambiguous—though clearly related to an academic department somewhere—“CSSD” has special relevance to Pittsburgh. As University literature describes it, Computing Services and Systems Development (CSSD) has long provided the “network infrastructure and telecommunications backbone for the University community,” offering among other forms of support, computer resources and training to students and faculty members alike.

The term “CSSD” is also unique to the Pittsburgh campus. The University, which today accommodates more than 28,000 students and a staff of nearly 5,000, further describes it as follows:

“Computing Services and Systems Development (CSSD) supports the teaching and research missions of the University by providing mechanisms (infrastructure, consulting, development and training) to students engaged in academic activities and to faculty in their laboratories and classrooms. CSSD is responsible for maintaining a contemporary IT environment, while exploring the next generation of technology, innovative computing, and telecommunication solutions.”

Only two pages of the document were released—a cover sheet and a second page pulled from one of the “email header” lists—so it is unclear precisely how much data the FBI may have acquired. There are clues, however, that suggest it may have been a substantial amount.

The page with Swartz’s email address is labeled page 26. When the FBI looked up the file, it noted the address was contained in Appendix A (“Computer Science”). So we know the first email header list takes up at least 26 pages, but maybe more. There is no reference to the size of Appendix B. The total size of the file, then, could be anywhere between 27 pages and 50 pages or 100 pages or 2,000—only the FBI knows for sure.

It is also unclear why Swartz was, presumably, in contact with a student or staff member in the PITT computer science department, though he is known to have been involved in multiple software development projects at the time, and had by then realized his own passion for collecting and sharing—frequently with other academics—datasets containing massive amounts of information, which he earnestly believed should be free and easily accessible to everyone.

“Information is power. But like all power, there are those who want to keep it for themselves,” he later wrote in his Guerrilla Open Access Manifesto. “Forcing academics to pay money to read the work of their colleagues? Scanning entire libraries but only allowing the folks at Google to read them? Providing scientific articles to those at elite universities in the First World, but not to children in the Global South? It’s outrageous and unacceptable.”

Gizmodo contacted the university in early November. After a week, PITT said it was still “digging” into the matter. On November 20, Gizmodo informed PITT that it was planning to publish a story stating that the FBI obtained the communications data of staff and students in connection with a terrorism investigation. Following that, correspondence from the University ceased for over a week.

In response to a later email raising the possibility that a National Security Letter was used to acquire to data on staff and students, a PITT spokesperson replied: “I’m afraid we have no comment.” The spokesperson would also not say whether the University had a policy of challenging the government gag orders that accompany NSLs, which are designed to prevent people and institutions from ever notifying the public about the letter’s existence.

National Security Letters

In 2007, the FBI would not have required a warrant to obtain the email headers from a public university. The Patriot Act, passed in the wake of the September 2001 terrorist attacks, significantly lowered the threshold for using NSLs and also made them much easier to acquire by expanding the number of FBI officials who could sign them. Today, the most senior agents at the FBI’s 56 nationwide field offices—special agents in charge (SAC)—are able to approve the use of an NSL.

NSLs may be used to acquire sans warrant a range of consumer credit information and other transnational records. But importantly, the statute authorizing their use in cases of electronic communications—under Title II of the Electronic Communications Privacy Act—do not permit the FBI to acquire the content of emails without a warrant. NSLs may be used, however, to acquire evidence in pursuit of secret warrants issued under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA), for developing evidence prior to the initiation of a terrorism investigation, and to corroborate information obtained by other means.

While the FBI informed Gizmodo that its use of such tools is governed by legal statutes and guidelines established by the U.S. Attorney General, the bureau has routinely violated and misinterpreted those guidelines, according to the DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel and the FBI’s own inspector general. Notably, these abuses were rampant around the time that the FBI appears to have acquired the PITT email data.

Between 2003 and 2006, the FBI reported the issuance of more than 192,000 letters, according to 2009 testimony before the Senate Committee on the Judiciary. However, the FBI’s inspector general also determined that this figure was also inaccurately low. A review of four field offices revealed the reported number of letters was, in fact, 22 percent lower than the actual number of letters issued. It also identified 26 possible intelligence violations, including the issuance of NSLs “without proper authorization.”

Out of 77 FBI files, the inspector general found that 293 letters had been used. Of those, 22 possible violations were discovered that had not been previously reported. The violations included “improper requests under the pertinent national security letter statutes” and “unauthorized collections.” Moreover, some of the justifications used to obtain the letters were overly convenient and inherently flawed.

The FBI Pittsburgh Field Office, which requested the analysis of the email headers linked to Swartz, also has a “troubling” history with regard to the monitoring of peaceful activists, notes a 2010 inspector general report.

In response to suspicions of illegal spying on anti-war activists raised by California Representative Zoe Lofgren, the FBI launched an internal investigation to determine whether it had targeted “domestic advocacy groups” based solely on activities protected under the First Amendment. Notably, even the issuance of an NSL cannot be based solely on observations of constitutionally protected speech. (Lofgren is, incidentally, the author of Aaron’s Law, a bill that sought to reform the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, under which Swartz was charged prior to his death. The bill did not pass.)

The inspector general’s report contradicted the 2006 congressional testimony of then-FBI Director Robert Mueller over FBI surveillance of a peaceful protest held in Pittsburgh four years earlier. While he claimed the bureau had a solid lead on a person of interest in a terrorism case, who just so happened to be a prominent local Muslim, the report found that the FBI had no evidence linking the man to anything. Even worse, it wasn’t until an agent was already undercover at the rally that the FBI learned he was there. Prior to that, it didn’t have “any reason to believe” he’d be in attendance, the report says.

“The fundamental issue with an NSL,” says Reporter’s Committee director and lawyer Gabe Rottman, returning to the subject, “if one was used in this case, is that the FBI can issue it on its own discretion and can collect pretty sensitive information, such as email headers.” But at the time, the FBI also claimed the authority to collect arguably much more sensitive data without a warrant or court order, such a person’s web browsing history.

It’s particularly worrying, he said, that the FBI can use what oftentimes turns out to be imaginary threats to national security as an excuse to stockpile U.S. citizens’s private data, even when no proof exists they’ve committed a crime. “Just as Aaron’s email was apparently picked up here,” he said, “you could have a reporter or some of their source information get scooped up and mined later. And that’s a matter of great concern.”

The perpetrators of this murder are still at large?