The prison system in America have introduced Scientology “re-education” jails to brainwash inmates using a controversial program of ‘Moral Reconation Therapy’.

According to an article on Raw Story, the church and prison system are keen to keep this hushed up:

A few years ago, Abe Bergman’s 19-year-old son was court-ordered into a residential treatment program in Washington State for co-occurring mental illness and “substance abuse.” After he’d been in the program about a week, Bergman called and asked: “Can I come visit my son?”

BYPASS THE CENSORS

Sign up to get unfiltered news delivered straight to your inbox.

You can unsubscribe any time. By subscribing you agree to our Terms of Use

The person he spoke to, a counselor, said: “No, he hasn’t earned enough points yet.”

“I thought,” Bergman says, “with someone with mental illness, wouldn’t it be good to have their family there? They said, ‘No. We run something call Moral Reconation Therapy here.’”

Bergman, a retired pediatrician and faculty member at the University of Washington, never was able to visit his son. He wondered, what was this mysterious-sounding “Moral Reconation Therapy” (MRT)? The term bugged him. It sounded like “trying to invent new words that don’t mean anything, but imply a certain specialness.”

So he talked to “six or seven mental health professionals—psychiatrists.” He asked them, “Do you know about MRT?”

None of them did.

He called the person who then ran the mental health office for Washington State. They’d never heard of it.

Finally, he talked to someone who worked in the criminal justice system. They’d heard of it, because MRT is used widely—according to the website of Correctional Counseling, the company that promotes and sells MRT—“in parole and probation, with juvenile offenders, in schools, halfway houses, drug treatment programs, jails, and venues covering the entire range of corrections.” It can also be employed “anywhere there’s substance abuse,” as someone associated with the program, who didn’t want their name used, told me.

In fact, according to the website, it is the primary drug treatment used in the US criminal justice system. MRT is used in all 50 states, and in six other countries besides the US. It’s on SAMHSA’s (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices, which helps states, community-based organizations and others identify recommended service models.

John D. Berg, M.Ed., LCPC, is a public health advisor with the criminal justice team at SAMHSA. He says that MRT is “one of the most commonly used [treatments] within drug courts because it fits well with criminal justice-involved clients we serve.”

Correctional Counseling says that its treatment has been administered to more than 1 million “offenders.”

So what is Moral Reconation Therapy? And why has no one outside of the prison system heard of it?

Moral Reconation Therapy: The Back-Story

MRT was developed by Greg Little and Ken Robinson, who met while studying counseling at the University of Memphis in the late 1960s, as Robinson describes in this video posted in 2015 “How Moral Reconation Therapy (TM) came to be:” The pair got jobs working in the Shelby County Correction Center in Tennessee: Little in the mental health unit, Robinson in the drug offender program.

There, they noticed that even “our best efforts brought people back.” So they wondered: “Are there not programs or tools that we can develop to help people permanently change their habits and lifestyle?”

They started “interviewing our failures”—those who returned to the program—and learned that the problem starts when people are released.

“When people leave that controlled area,” Robinson says, “and you expect them to generalize [what they’ve learned] in the brave new world, people have a tendency to slip back to their old ways of thinking.”

Robinson and Little continued to develop and test MRT between 1979 and 1983 at the Federal Correctional Institute in Memphis. In 1990, they establish Correctional Counseling a “free standing privately held company” to “design, research and implement programs that can make a difference in people’s lives.” Robinson (below, left), who went on to get his doctorate in educational psychology, remains the president of Correctional Counseling today.

Little (below, right) has taken a slightly different path. He’s now a “Paranormal Investigator, Ancient Mystery Explorer, Documentary Filmmaker, UFO Theorist, Author and More.”

Little and Robinson assert that “clients enter treatment with low levels of moral development, strong narcissism, low ego/identity strength, poor self-concept, low self-esteem, inability to delay gratification, relatively high defensiveness, and relatively strong resistance to change and treatment.”

According to this theory, these traits lead to criminal activity. In contrast, those who have attained high levels of “moral development” are not likely to behave in a way that is harmful to others or violates laws.

Moral Reconation Therapy reflects the idea that people who end up incarcerated are morally inferior—and that is why they are in a prison. It’s an idea that anyone familiar with the history of the War on Drugs, for example, would reject. And the more I investigated MRT, the more I found there was something significantly wrong with this program—and that no one seemed to realize or care.

MRT’s Strange Materials

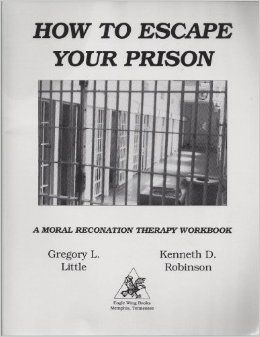

The main MRT manual used across the country, given to every participant, is called How to Escape Your Prison.

The prison the title refers to—the real prison, the authors say—is your own personality.

It’s “designed specifically for offenders” (p. 38). And according to Dr. Ken Robinson: “Offenders do really think differently. They see the world quite differently than you and I.”

Other language and images throughout the text reiterates the idea that people who are incarcerated are inferior to those who aren’t.

They’re inferior intellectually:

“We might add that the words you read here are simple enough for anyone with half a mind to understand” (p. 16)

“if you think you know something about psychology, just put it aside for a while. What you think you know will only confuse you” (p. 17)

But most importantly, they’re inferior morally. And the fact that they’re incarcerated—and this is key—is only their fault, no one else’s:

“You have probably become aware of the sorry state of your life and the fact that you, alone, are responsible for where you are.”

“The large majority of those reading this book need to begin at Step one because they are in the box of disloyalty. We estimate that 90% of this book’s readers are there. (Sorry- but if we told you differently, we would not be doing you a favor)” (p.36)

“If you can’t do Step 1, it simply means you are not ready to change. It means you are dishonest and can’t be trusted. And it also means that you want to stay that way” (p. 40).

The theory creates a double bind that leaves no way to disagree, challenge or critique the contents themselves. If you disagree with the contents of the book, you’re automatically just dishonest and don’t want to change.

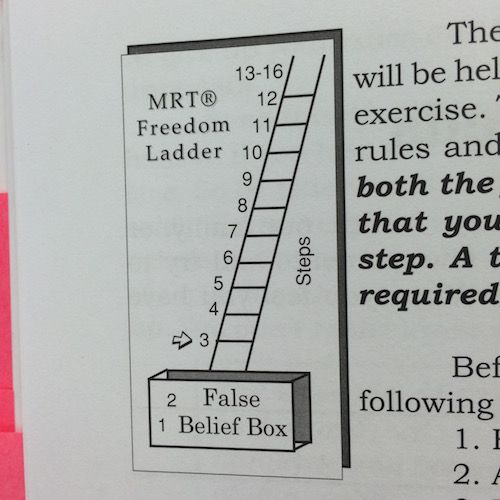

There’s also an underlying pseudo-Christian element, like this”original sin”-ish part: “Immediately upon your birth, you “fell from grace” and began your descent down the freedom ladder.”

The highest level one can achieve in terms of morality on the freedom ladder is a state of “Grace,” a stage in which “one must give oneself to a major cause.”

The moralizing, vaguely religious rhetoric throughout the workbook is accompanied by slightly bizarre cartoons. Many are comically outdated—as if they were made on WordPerfect in 1993—some are disparaging of people who are in prison, and some are just odd.

The vast majority of people (as opposed to fairies or monsters) depicted in the book are white—odd in a system where nearly 80 percent of people in federal prison and almost 60 percent of people in state prison for drug offenses are black or Latino.

Semantics and Scientology

When I put to multiple people associated with Moral Reconation Therapy that people might balk at equating morals with laws, with teaching “morality” as a therapeutic treatment, they explained that the “moral” in MRT actually comes from Lawrence Kohlberg’s theory of six stages of moral development. On their website, the authors state, as if anticipating this concern: “In this case, ‘moral’ does not refer to a religious concept, but rather the theoretical conceptualization of psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg.” In their workbook, the authors say that they draw on the work of Kohlberg, as well as a range of other well-known theorists like Carl Jung, Erik Erikson and Jean Piaget.

MRT has, depending on interpretation (some stages incorporate sub-stages), nine-to-16 levels of morality, ranging from “Disloyalty,” the lowest, to “Grace” (the highest). These stages—which don’t appear to share anything in common with Kohlberg’s stages (more on that soon)—make up the “MRT Freedom Ladder.”

What about the made-up-sounding word “Reconation”? Little and Robinson write:

“Prior to common usage of the term ‘ego’ in psychology in the 1930s, the term ‘conation’ was employed to describe the conscious process of decision-making and purposeful behavior. The term moral reconation was chosen … because the underlying goal was to change conscious decision-making to higher levels of moral reasoning.”

Conation is in the Merriam-Webster dictionary as “an inclination (as an instinct, a drive, a wish, or a craving) to act purposefully.” Reconation is not in the dictionary.

There’s also something in MRT’s requirement of the acceptance of personal transgressions that is reminiscent of the 12 Steps of Alcoholics Anonymous. I askedInfluence columnist Maia Szalavitz, a journalist with decades’ experience covering subjects like mental health, addiction and addiction treatment, for her thoughts on MRT: It “shares all the negative results that people can get from 12-step programs in terms of moralizing,” she told me. “We don’t tell people with actual diseases that it is caused by their sinful nature—yet the implications in MRT seem to be that you chose to be a criminal, and it was your thinking that was wrong, and society was completely blameless. Trauma has nothing to do with it. It really cannot possibly be trauma-sensitive. Right there is a huge problem.”

MRT’s creators are adamant that their program is quite distinct from 12-step programs, though (and the similarities are not pervasive). They prefer to consider MRT “evidence-based” and a “cognitive-behavioral” treatment.

Instead of associating themselves with the 12-step movement, in the acknowledgments section of How to Escape Your Prison, Little and Robinson credit a man named Ron Smothermon with giving them the names and framework for the stages on the Freedom Ladder. Smothermon appears in online searches as a kind of self-help guru, author of texts such as Winning through Enlightenment, The Man-Woman Book and Conversations With Life.

He seems to have some associations with cult-like movements, particularly EST(Erhard Seminars Training), a self-help program trendy in the ’70s, and its repackaged descendent, the Forum (which was succeeded by Landmark, a more mainstream management training program, which today has clients like Reebok, Microsoft, NASA and Lululemon).

When the word “Scientology” began cropping up in my searches in connection with Smothermon, I delved deeper, and suddenly noticed a shocking similarity, one that was clearly not coincidental: MRT’s Freedom Ladder is an almost direct replica of Scientology’s “Life Conditions.”

Both include the stages, in the same descending order, of: “Normal,” “Emergency,” “Danger,” and “Non-Existence.”

Then, Scientology has “Liability, while MRT has “Injury;” Scientology has “Doubt” while MRT has “Uncertainty;” and last, Scientology has “Treason” where MRT has “Disloyalty.”

The Scientology Handbook says that the “conditions” are “states of existence.” There is something called the “ethics conditions” which “identify these states and provide formulas—exact steps which one can use to move from one condition to another higher and more survival condition.”

“Ethics is the means by which he can raise himself to a higher condition and improve his survival.”

Then the handbook gets into some intricate graphing—apparently you can graph your “statistics” to see what “condition” you are in—and takes off into some nonsensical but pithy warnings, like: “Correct scaling is the essence of good graphing” and “The element of hope can enter too strongly into a graph.”

MRT, thankfully, doesn’t seem to have incorporated the “statistics” component of Scientology’s “conditions” into its “Freedom Ladder.”

There’s a lot from Scientology it seems to have left behind. And overall, MRT seems less like a part of some nefarious Scientology plot to infiltrate the prison system, more a mish-mash of psychobabble picked haphazardly from 1970s self-actualization talk, Christianity, AA and yes, Scientology.

A Secretive Organization

I wanted to find out more about this strange book that has been forced on a million people in the prison system, this book that uses terms and ideas from Scientology and tells people that their immoral personalities are responsible for their substance use, their incarceration and their unhappiness.

But for an organization that purports to seek to help as many people as possible, Correctional Counseling keeps its materials mighty close to its chest.

When I tried to order some books from their website, I was informed that only people who have undergone the patented MRT training can even order the book. Basic trainings cost around $600 to attend.

Correctional Counseling advertises heavily to drug courts. And if the drug courts don’t want to pay for the manuals and training fees? Correctional Counseling reassures them in one of the advertisements linked to in its newsletter: “Many drug courts require clients to bear the costs of workbooks and groups.”

MRT’s representatives seemed pretty secretive, too, when I tried to reach them.

The first reaction of the Correctional Counseling representative who picked up the phone was suspicion: “How did you find out about MRT?”

She asked me several times who I was and what I was interested in writing about, even though I’d already simply told her that I was a reporter interested in writing about MRT. She then said that a clinician would email me; he never did. So I emailed them—no response. I called and left messages multiple times. One person did speak to me then, but only off the record.

Finally, instead of continuing to ask for Robinson himself, I requested Steve Swan, vice president of Correctional Counseling.

Swan emailed me. The subject line was: “I hope the attached information is helpful in response to your question.” The body of the email was a link to a 2000 article on MRT and its success.

I replied that I had some questions, and was planning to write an article that touched on some concerns about the program’s moral component. I wrote that I would love to include a defense of MRT in my article.

He replied:

“I don’t really have anything else that I can add. You might view some of the interviews that both Dr. Little and Dr. Robinson have posted at the following link: [here]. It might provide some clarification regarding some of your questions.”

I had already seen the videos. I wrote: “Do you all still stand by the statement in How to Escape Your Prison that 90 percent of people in prison are in the lowest level of morality, i.e. the stage of ‘Disloyalty’?”

No answer.

Lastly, I gave him an opportunity to respond to the strong similarities between MRT’s Freedom Ladder and Scientology’s Life Conditions.

No answer.

Goldman Sachs Funded MRT

MRT has mainly operated under the radar, in courts, mandated treatment programs, jails and prisons—those institutions described by Angela Davis as “black hole[s] into which the detritus of contemporary capitalism is deposited.”

I first came across it in my previous occupation as a social worker, being used at an “alternative to incarceration” program, where it was taught to a mix of people who had been convicted of drug-related crimes—some who struggled with problematic substance use, and some who had been caught selling drugs but said they had an addiction problem in order to decrease or avoid jail time.

Though the agency where it is used professes a desire to provide “trauma-informed care,” (the buzz-phrase of the day), and to use respectful, person-first language, only a few people other than me seemed to flinch at the language and implications of these strange books.

MRT did receive slightly more attention, at least superficially, last year, when it was reported on as the intervention chosen in the first ever “Social Impact Bond” in the United States.

The much-heralded “social impact bond” (SIB) uses money from private funders to pay for public policy programs.

The very first SIB private funder was Goldman Sachs, which contributed $7.2 million to launch the Adolescent Behavioral Learning Experience (ABLE) in Rikers Island for kids aged 16 to 18.

Goldman Sachs and the team it employed chose MRT as the treatment model.

Why?

MDRC, a private nonprofit policy research organization, was chosen to serve as intermediary between the funding source and the program itself. David Butler, vice president at MDRC, told me that in choosing a program, “a lot of research was done on group cognitive behavioral therapy programs as a way to reduce recidivism.” They looked at meta-analyses and concluded that “MRT was the best bet.”

Butler acknowledged that the study showed no significant difference in effectiveness among CBT approaches, and explains that they chose MRT simply because it had an open structure, where people could go in and out, join at different times. People move around so much at Rikers, he says, with stays of such varied length, that this was important.

“In retrospect,” Butler admitted, “it didn’t work.”

But what about those meta-analyses saying it would be the best bet?

Well, first of all, there was very little evidence that MRT worked with juveniles. A 2009 study, “Evaluating the effectiveness of Moral Reconation Therapy with the juvenile offender population,” found “no significant differences in recidivism between the treatment group,” (MRT) and “the comparison group” (no MRT). And, as Wilson et al.found in an evaluation of MRT and other programs: “three of the four methodologically stronger studies [for adults] were conducted by the developers of MRT”—Little and Robinson themselves—“raising the question of whether the findings generalize to MRT programs run by other program personnel.”

Butler dismissed the idea that these studies were biased.

Rather, he said, it’s likely that no CBT program would have worked in this experiment because “the conditions at Rikers were so bad in so many ways, that having people 4-5 hours a week just wasn’t going to offset [that]. Interacting with officers who can be pretty abusive… People may say, ‘it wasn’t implemented correctly,’ but we did a lot of quality control, monitored classrooms and they were sticking closely to the way it’s supposed to be implemented.”

Could it be possible that the program failed because of the cognitive dissonance a person might experience as a result of being told they’re incarcerated due to their low moral reasoning, while they are under the control of officers who, to use Butler’s words, “can be pretty abusive”?

“I think the rhetoric of the program can be criticized on those grounds,” Butler said. “But when people delivered the program they stay away from the rhetoric of moral judgment. They did not emphasize that.”

So the program has to be implemented as intended in order to work, but the whole “moral” aspect of Moral Reconation Therapy was conveniently ignored by the people who implemented it?

This kind of slippery logic was becoming familiar.

Personal Interventions for Structural Problems

But perhaps any CBT program—an umbrella term for programs that focus on changing a person’s thinking and behavior—would be on slippery ground in our prison system, where so much incarceration results from racism and poverty.

As Butler acknowledged: “All CBT programs have at their root the notion that you have to take responsibility for your condition. If you’re not willing to do that, if you continue to see yourself as a victim of circumstances, a victim of your race…These programs don’t explain the world. It’s clearly not solely an issue of their moral turpitude. Certainly all factors like poverty, police violence, racism … play their part. But how do you address those with an intervention targeted at the population themselves?”

“If you listen to people who have been successful [after incarceration],” he continued, “and you hear the way they talk about what their success has been about—it’s been about taking responsibility, resisting influence of peer groups … You hear that from ex-offenders all the time. Clearly it doesn’t explain why we have so many people in prison, but it is a set of tools that can help people move ahead when they get out.”

Still, there’s a chasm between giving participants a sense of agency over their lives, and telling them that they are morally inferior.

I made the point to Butler that interventions aimed at harmful existing structures might do more to help this population than individual-level interventions—a point he said was “well taken.”

This was articulated better than I could in an article by Jarrett Murphy, one of the very few that criticized the SIB experiment at Rikers (most media, like the New York Times,took the line “Despite the failure of the program, the experiment succeeded in blazing a new trail.”)

Murphy wrote:

“Is the main driver of youth recidivism a lack of social skills, a deficiency of personal responsibility or an epidemic of poor decision-making? Those are certainly factors in many youth arrests. But is someone picked up in a trespassing sweep in a friend’s building displaying a lack of responsibility? Is a youth who’s homeless really able to make decisions that keep him out of the criminal justice system?”

The answers to these questions are obvious.

As Robert Lake, a professor at the School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, writes in an analysis of the Rikers SIB:

“…deep-seated societal reform [that addresses issues like “structural inequities or institutional practices”] is not only ignored, but is likely to be actively resisted as destabilizing of the structural privileges that establish a financier class able to realize the profit to be made by investing in SIBs.”

Lake’s concern is that the financial industry’s interests overtake, and are structurally at odds with, social programs that address problems at their root.

So in a sense, MRT was the perfect choice for a Goldman Sachs-government partnership program: Its underlying logic props up the structural status quo, which ultimately benefits the very bankers funding it. Interestingly, one of the early studies “proving” MRT worked was paid for by a Koch brother (conducted by the Koch Crime Institute).

I doubt any of the reporters who wrote about the Rikers SIB had actually read any MRT literature—because it’s hard to get, and if anyone had actually seen it, they would have likely mentioned the cultish elements.

MRT, the government-recommended treatment program for substance use issues in the criminal justice system, is a mish-mash of Scientology-infused psychobabble and neoliberal moralizing used to keep poor people of color in their place. Did anyone elseknow about this?

People Who Have Experienced MRT

On the Correctional Counseling website there are links to dozens of articles, with staff and a few participants in different court-mandated treatment programs and jails praising MRT.

One article profiles a mandated drug treatment program in Modesto, California. It quotes Larry Muir, who was sent there after being released from the most recent of five prison terms he’s served for drug charges over the course of 25 years. “I went to a party when I was 20 and I came home when I was 45,” Muir says.

He says MRT is helping him get his life together this time: “If you take the drugs and alcohol out of a person, they still have character defects–the mentality, the thinking, the way they act. If they don’t work on those, it’s going to be tough.”

Another article quotes Shantee Jimenez, a client at the Day Reporting Center: an “intensive combination supervision-training-education program” in Bakersfield, California, that is “dedicated to keeping folks like Jimenez”—those on probation following felony convictions—”on the straight and narrow.”

She also says that MRT helped her: “I was manipulative. It was going to be my way. That’s where criminal thinking comes in. I had to learn that my way wasn’t the right way.”

The article adds that “Jimenez, who has been in DRC since her release from jail in April, was supposed to have graduated from DRC this month. Because of her behavior, however, that didn’t happen.”

She says: “I thought everything was everyone else’s fault. I had to realize it was me.”

There’s little reason to doubt that they (and the counselors who treat them) are sincere. And Correctional Counseling claims, on their more contemporary looking, reader-friendly website called “MRT Centers,” that: “Studies show MRT-treated offenders have re-arrest and re-incarceration rates 25% to 75% lower than expected.”

But there are also those who have been through MRT and have less than positive reviews. For example, “Eric R.” writes on an online forum:

“These people who are the ‘treatment staff’ are the most dishonest liars and out and out cheats I have ever met…They don’t earn an honest pay check, they steal it by fostering a program that is harmful to those forced into it…Moral Reconation Therapy is a huge ripoff copy of AA. The last page of their treatment manual says it all, “state of grace”, and artistic references to the bible, easter lillies, palm fronds, candle stick with a candle lit, and a copy of what is obviously a bible rendered as a page dress up suggestion of what MRT is really all about, get religion now while we can still “save” you. This MRT manual is a monstrosity…”

On another forum was “Wahig,” who identified as a “counselor in a corrections environment, but I don’t buy the program hook, line, and sinker.” He was posting to try to find out more about MRT, which was used in the program he worked in. He writes:

MRT purports to be based on Kohlberg’s stages of moral development, but it doesn’t pan out. I have a graduate degree in counseling and I choose to work in community corrections because I honestly believe I can help people there. I do my best to serve court-mandated substance abuse clients in a daily treatment setting. The core of our program is MRT. MRT does not specifically focus on alcohol or drug abuse. MRT focuses on changing one’s “personality” from one based on criminal thinking to one based on “higher ethical principles…I am in the midst of reading Inside Scientology, by Janet Reitman. It was there I found that “The Conditions” of Scientology bore an uncanny resemblance to MRT’s Freedom Ladder. I have found that they may have a common source, but I’m still doing some research.”

Jeremiah Bourgeois is another person who has been through MRT. At age 14, he was sentenced to a mandatory term of life without parole for shooting and killing a man who had testified against his brother in a court case. Now 38 years old, he has been working toward a bachelor’s degree and studying law while in prison; he even published a law article in the Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law. In one section, he focuses on MRT:

“The premise behind this therapy is that there is some elementary defect in prisoners that thirteen weeks of banal advice and reproach will mend. Never are the roles of social and economic inequities considered.”

“The program is designed to convince prisoners that their lives are a direct result of their poor choices, for which they must finally learn to take responsibility. As the prisoner works his way up the ‘MRT Freedom Ladder,’ moving from a ‘state of disloyalty’ to what, in an astonishing vulgarization of Christian doctrine, they call a ‘state of grace,’ the authors repetitively drum this theme home.”

SAMHSA Doesn’t Seem to Know Much About the Program It Recommends

How can SAMHSA, the federal government’s organization devoted to treatment for substance use issues and mental illness promote and funnel money towards MRT?

John D. Berg, M.Ed., LCPC, is a public health advisor with the criminal justice team at SAMHSA’s Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. He was, unlike the folks at Correctional Counseling, kind enough to talk to me. But he didn’t have many answers about MRT—even though it’s included in SAMHSA’s list of evidence-based treatments that are recommended for its grantee programs.

I asked him how Moral Reconation Therapy, with its statement that people engage in problematic substance use due to low levels of moral reasoning, could mesh with SAMHSA’s assertion that addiction is a “brain disease.”

He said: “It’s a good point. I haven’t had anyone raise that with me.” He told me that he wanted to “check with our providers” because he was now “a little curious” himself.

“It definitely isn’t looked on as a moral failure” he told me. “We are not encouraging that anyone look at it that way at all.”

Unfortunately, by promoting MRT, SAMHSA is doing just that.

I also asked Berg about the clearly recognizable overlap between MRT and Scientology. He seemed surprised. He told me to let him know what I found out—he’d be curious to hear.

Moral Reconation Therapy Is Spreading

In the meantime, MRT is extending its reach. As the anonymous Correctional Counseling representative told me: “Oh, we are definitely growing, you know, we just want to help as many people as we can.”

In view of all I learned, this is concerning, to say the least.

Instead of shooting money into pseudo-rehabilitative, pseudo-Scientology “treatments,” couldn’t we put it toward more helpful things? Like bail reform: 79 percent of people in Rikers have not been convicted of anything; they’re only there because they can’t afford bail. Or a cause for which Abe Bergman, whose son underwent MRT, is now a public lobbyist: supportive housing for people with mental illness.

“You have probably become aware of the sorry state of your life and the fact that you, alone, are responsible for where you are,” states How to Escape Your Prison.

Really?

Perhaps the proponents of Moral Reconation Therapy should turn their focus from their “target populations” and instead check at what level of the “morality ladder” they find themselves.

I have a feeling they may be in the Box of Disloyalty.